Appropriate limits will enhance creativity and make you more effective in fulfilling the mission of your organization.

As a fundraising professional, especially one in a small organization that is awash in opportunity, it can be tempting to want to do everything. “The mission needs me!” Believe me, I get it.

If you’ve ever felt overwhelmed by the prospect of funding your mission, this essay is for you. Keep reading for stories from the Amazon rain forest (Teddy Roosevelt nearly died because a narcissist ignored mission limits), raising ten times more than a failed tactic with one email send, and using your limited time to greatest effect as a fundraising professional.

In this essay, we are exploring appropriate limits, which we can define as those boundaries which are natural to you and I as individuals and to the organizations we inhabit. At their core, appropriate limits remind us that we are created beings. This is a concept which humans have been frustrated by since the Garden of Eden, when the Adversary whispered in Eve’s ear that they ought to be set free from the way they were created to be. When limits are functioning well, they will shape creative vision, give scoreboards to our efforts, and function as a hedge against overwhelm and burnout. Limits in this sense are like the boundaries of a well-tended garden. They do not inhibit growth or interfere with health, but rather define the conditions which encourage flourishing. A proper view of limits will enhance creativity, and increase efficacy in fulfilling the mission of the organization.

You are a designed being with appropriate limits.

I drank a lot of caffeine my first year as a director of development. The organization I was working for took a chance on hiring an enthusiastic 21-year-old who was passionate about their mission of promoting life. As we entered the final month of the year, I often walked into the gift processing office at our headquarters and checked in with our gift processor, Cori. It quickly became obvious to her that I was stressed out about whether I was doing enough to encourage the supporters of our organization to give. I was mentally placing the burden of the funding of the organization entirely on my shoulders. She gave me some words of wisdom I’ll never forget.

“Jon, God always provides enough. I’ve been working here for 20 years and he’s always been faithful to give us what we need.”

The pressure I felt to continue pushing beyond my personal limits of health and stress in that first year-end situation was driven by two main factors. First off, I had an appropriate enthusiasm and belief, which motivated my urgency. Secondly, I had an inappropriate locus of control, thinking I was the one fully in control of giving, which motivated my stress. As a nervous but ambitious development director, I realized after Cori’s gentle correction (and often continue to realize when my wife reminds me) that I wasn’t in control of other people’s actions. As fundraisers, we are intentional in our actions, our messages, and our offers but we don’t control the giving actions of the supporter.

It is an act of trust to do our best in a situation and then rest.

Embracing your limits involves knowing what your best is, doing it, and then leaving the rest to a God who knows more than we do.

As a note, there are situations where individuals are wrongly incentivized or duplicitously pushed into exceeding personal limits on behalf of a mission. This essay won’t cover those types of extenuating circumstances in depth.

Shift focus with me from the personal perspective to the organizational perspective and you will see that limits on the organization become imperative. Nonprofits have intense belief in a cause, and are appropriately involved in affecting change in the world based on their beliefs. However, there must be reasonable limits that match the extent of the change that is desired, or the mission becomes unpalatable to supporters. If a local organization doesn’t communicate the limits of their service area, supporters are stuck wondering if they are actually giving towards the need in their community. If a visionary nonprofit starts using “change the world” language without proper limits, the staff and supporters are left wondering what step one in the plan to do so could possibly be.

In this way, a limit structure gives meaning to the mission.

We sometimes choose inappropriate limiting beliefs.

The thesis of the first essay in this series (Manage Your Beliefs) might seem at odds with the second. To review, here is that thesis: As a leader, your beliefs start internally through mental repetition, are validated externally in the sphere of action, and affect your organization as you set culture. If nonprofit leaders and fundraising professionals are to intentionally manage their beliefs upward, how does that jive with accepting limits on the mission? Shouldn’t we be busting through those limits and achieving new and exciting innovations in pursuit of our mission?

Let’s clarify. Appropriate limits ought to be distinct from limiting beliefs. If a fundraising leader chooses to believe that a top supporter is “maxed out” they are less likely to present the full missional need to that supporter. If a new fundraiser is constantly checking whether their supporters like them because they have a limiting belief that their likability needs to precede any giving, they may fail to be bold in making the ask. If a leader takes the perspective on an individual’s personal growth that they will never change, they are less likely to give them the opportunities necessary to continue growing. Limiting beliefs are chosen, and can be jettisoned. Sometimes limits need to be tested or suspended, times known as liminality, and a conversation around how leaders can carefully guide their teams into and out of these spaces occurs at the end of this essay.

Externally imposed limits often lead to creative innovation.

Fundraisers and leaders are often placed in circumstances with limits beyond their control. How the individual responds in this situation says much about their character. The reality is that a managed belief like “there is a creative solution available,” or the question “what opportunity does this limit present?” shapes conversations around positive forward-facing action.

Let’s explore three true examples, two from the nonprofit world as well as a classic sports tale. First to a recent nonprofit experiment. On January 18th, 2022 the Amazon corporation announced the closure of their corporate responsibility program, AmazonSmile. The program had allocated a small percentage of sales on select products to give towards charitable organizations. In the ensuing industry conversations, Tim Kachuriack challenged me with this creative reframe: “This actually creates an opportunity for fundraisers. If your organization has benefited from the Amazon Smile program in the past, send a message to your donors to inform them that the program has been canceled and ask your supporters for a gift to help bridge the gap in lost revenue from the program. My bet is that this one appeal alone would generate more revenue for the organization than they received from the program. I’d be curious if that hypothesis is true.”

Over the next couple of days, I wrote an email template articulating this message and shared it publicly online. Dozens of organizations used it, and at my organization, Summit Ministries, we sent it out with a specific monthly donation ask. Here are the results. In 2022, a group of amazing donors made $8,494.60 in purchases through the Amazon Smile program. Because of this, the corporate foundation contributed $424.73. After sending the email appeal, the organization received several monthly contributions that came to a yearly total of $4,620. This creative reframe generated ten times the revenue on an ongoing basis. I heard from several other organizations, like Jen’s:

“Thanks for the AmazonSmile appeal post! It worked….I e-blasted a version to our small virtual database and generated one recurring gift for 12 months that will exceed the programs annual earnings for our organization… PLUS, we saw another $1050.00 same day from the call to action! Certainly worth the 1.5 hours to create and share this appeal.” – Jen

In the context of Amazon’s externally imposed limits, asking the question, “How can this be reoriented around relationship building?” was a forcing function for creativity. Another creative question to ask is “What does this limit tell us about the realities of fulfilling our mission?” That’s the topic of our second nonprofit example, shared in Leah Kral’s outstanding book, Innovation for Social Change: How Wildly Successful Nonprofits Inspire and Deliver Results.

Worldreader is an organization that works with their partners to get children reading at least 25 books a year with understanding. When the organization launched in 2010, they had arranged a dream partnership. Amazon corporation underwrote their efforts to provide Kindle E-readers for a pilot group of elementary school children in Ghana. Yet after only a few days of use the pilot program ground to a halt. The students found that their kindles were breaking during recess and free play.

Taking this limit on fulfilling their mission in stride, Worldreader began two separate tests. They made plans for ruggedizing the Kindle e-reader to handle elementary school treatment. In addition, enough of their students had access to mobile phones, so they began concurrent development on an eReading app.

Paying close attention to budgetary limits, Worldreader pursued both tracks and noticed that thousands of people began using their new mobile application. Over the ensuing years, the app was iterated on many times over to ensure missional adherence and to incorporate user feedback. Today, over 185,000 users every month use the Worldreader platform.

Sometimes though, organizations find themselves in truly extreme situations. This is where we find our third and final example of external limits being used to spur creative opportunities and can potentially become the basis for best practices.

In 1968, the NFL conducted an expansion – pulling unwanted players from existing teams onto the roster of the newly formed Cincinnati Bengals. The team chose Bill Walsh as their offensive coordinator and when he walked onto the practice field he realized he was dealing with “comically inadequate players.” Not to be deterred, Walsh began crafting a new approach to NFL offense due to the limits placed on his strategy. He began by throwing out the conventional wisdom of running his “biggest” players directly against the tough, physical, mean defensive players on opposing teams. Walsh had another realization. His quarterback, Virgil Carter, had a terrible arm. “Virgil,” Carter was once told, “if you want to throw the football more than 20 yards you better fill it with helium.”

These limits became the basis of the “West Coast Offense.” Walsh built a playbook full of passing routes that bypassed the big slow defensive lines yet were short enough to manage the weak arm of Carter.

“No helium was required,” Walsh joked.

These “comically inadequate players” went on to win the AFC Central division two years later under Walsh’s leadership. The West Coast Offense became a full philosophy when Bill Walsh, now the head coach of the 49ers (the worst team in the NFL at the time) shockingly picked Joe Montana in the third round of the 1979 draft. The scoop from the scouts that year was that Joe, “Was too small and had too weak an arm to play in the NFL,” Michael Lewis writes in The Blind Side: Evolution of a Game. In Walsh’s system, Lewis continued, “[Montana] would become, by general consensus, the finest quarterback ever to play the game.”

Years later, as assistant coaches and coordinators were recruited out of Walsh’s 3-time Super Bowl winning 49ers organization, they brought the West Coast Offense around the NFL and it became the conventional wisdom.

“It all started,” Walsh said, “When I was forced to use Virgil.”

As a nonprofit leader, you may feel similarly about the team you’re called to lead. Or you may look through your donor relationship management software at what seem to be “comically inadequate players.” There may be more there than meets the eye. If you are wondering where to start in that sort of context when faced with limits on your time, that’s the topic to which we will turn next.

Maximizing effectiveness while being realistic about internal or personal limits leads to greater personal and organizational efficacy.

The limits on your responsibilities as a nonprofit leader or fundraiser informs how you design your day. A proper view of limits allows for categorization of personal effectiveness. In choosing to lead yourself as a fundraiser well, you must choose healthy limits on your time and activities. If there were unlimited time and opportunity as a fundraiser, it would not matter how you spent that time since there would always be the possibility for connecting later. As a steward of your salary at the nonprofit organization, you are responsible for the use of those dollars to achieve missional outcomes. As fundraisers, this means transforming the financial inputs of our salaries into relational actions that inspire generosity among supporters.

In manufacturing, the concept of the Theory of Constraints (TOC) was created by Elihu Goldratt to identify how complex systems run more efficiently. The core concept of the Theory of Constraints is that every process has a single constraint and that “total process throughput” can only be improved when the constraint is improved. A nonprofit development program is a complex system with many potential constraints. A goal of an effective coach, consultant, or leader within the department is identifying whichever constraint is currently limiting healthy growth. They then make improvements to the constraint factor with available resources, as well as optimizing the system around this constraint.

For this next example, think of your time as the main constraint to be maximized. In your pursuit of personal efficacy as a fundraiser, consider this C/I Framework from Tim Gunsolley for how to steward key relationships.

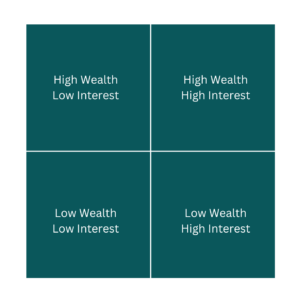

Imagine a two by two grid broken up into four quadrants. Along the Y axis (bottom to top) you see at the bottom “Low Capacity to Give” and at the top “High Capacity to Give.” Along the X axis (left to right) you see on the left “Low Interest in your Cause” and on the right “High Interest in your Cause.” If you want to be more specific or plot someone individually into this graph, think of the X as scales from one to ten.

There are people who are High Wealth, High Interest – Top Right

There are people who are High Wealth, Low Interest – Top Left

There are people who are Low Wealth, High Interest – Bottom Right

There are people who are Low Wealth, Low Interest – Bottom Left

Each of these quadrants should inspire a different strategy. As a fundraiser, your responsibility isn’t just to call the people who are excited to hear from you. your responsibility isn’t just to call the people you like the most. your responsibility isn’t even to call those who love the mission the most. As a fundraiser, you are responsible to provide for the needs of the organization by offering those who have high giving capacity and high interest in your cause the chance to participate in a worthy mission.

Of course, being relational and caring well for those who are not in that top right quadrant is imperative. Your time spent in those other quadrants needs to be limited because you must be realistic about the limits that are placed on your time and choose well within those limits.

The people who are “Low Wealth, Low Interest” should be treated with respect and care when you encounter them. But as a fundraising professional stewarding limited time, it is a mistake to spend much time in this category. Consider the phrase, “Bless and Release” as representative of your attitude here.

The people who are “Low Wealth, High Interest” are likely the largest cohort of individuals that you will encounter in your work a fundraiser. They are outstanding men and women who love what you do, and joyfully participate when they have the means to do so. “Appreciation” should be your go to response when interacting with this group of people, since you never know when their situation may change, and because their ultimate worth is not dependent on their net worth. Within reason, time spent in this quadrant is almost never wasted.

The people who are “High Wealth, Low Interest” can be a tempting group of people for you to focus on. The main idea here is “Cultivation.” Yet here is a cold reality. The fundraiser who spends their time wishing they had billionaires to call is unlikely to raise money from the millionaires they already know. Beware the temptation of spending all your time in moonshot attempts to get a hold of someone on the Forbes list. There is a time for following your intuition, but as a good steward of your limited hours, consider taking a step towards relationship with these individuals and watching to see if there is any reciprocal interest. If not, you may need to continue the cultivation process through less time-intensive methods like making sure these individuals are part of your marketing efforts.

The people who are “High Wealth, High Interest” represent the quadrant where your time is most effectively spent. This quadrant requires courage to ask your relationships to “Deploy” their wealth into the mission they care about. Our third essay in the series will explore more activation strategies for key relationships and about how cultivating a culture of gratitude sets the stage for effective deployment.

Recognizing internally imposed limits helps identify the highest and best use of your time within fundraising activities.

Liminal space allows for a temporary suspension of limits, but humans are not designed to function indefinitely in liminal environments.

Sharp eyed leaders will notice a gap in this essay so far. There are times when the limits of an organization need to be suspended in order for creative solutions to be explored. The limits of an organization become rigid when they are never challenged. Ossifying organizations fail to recognize changes in the environment and more nimble teams end up with the growth and opportunity.

This part of the exploration centers on the concept of liminality.

“Liminal space is the uncertain transition between where you’ve been and where you’re going physically, emotionally, or metaphorically. To be in a liminal space means to be on the precipice of something new but not quite there yet. The word “liminal” comes from the Latin word “limen,” which means threshold.” – Theodora Blanchfield, AMFT

These threshold spaces are important. Creative visionaries go into the unknown and return with possibilities that are as yet uncreated pass through liminal space regularly. These leaders navigate these spaces most and tend to have a picture for what the organization could be in the future when it’s carefully pursued.

Careful leaders who take their organizations intentionally into liminal space need to provide a timeline for those who are made uncomfortable by extended stays in the realm of relative chaos or uncertainty. The COVID-19 pandemic was a recent example of a culture-wide liminal event where the norms of the culture were put into uncertain transition. Leaders who recognized this situation provided guideposts and established new norms for their teams within the liminal space while asking their team members to look for the opportunities provided by the threshold moments.

In the same way that you and I do not live in the beautiful atrium of a museum, liminal spaces provide the opportunity for new experience but they function poorly as a permanent residence. Liminal spaces have the potential to inspire us, when carefully stewarded.

Negative Example. Narcissism leads to ignored limits and danger for all those involved.

The consequences of ignoring limits can be catastrophic.

After Teddy Roosevelt lost the 1912 Presidential election, he intended to reset his mental state by challenging himself with a robust physical adventure in the Amazon rainforest. He had the unfortunate circumstance of choosing a narcissistic expedition partner, Father Zahm, who imagined himself exempt from the ravages of the rainforest. Zahm naively chose a faltering arctic explorer, Anthony Fiala, as the quartermaster of the tropical rainforest expedition. He later tried to get the Brazilian expedition laborers to carry him on their shoulders during the initial hikes to the start of the river descent. When Roosevelt recognized the toxic nature of his expedition partner, he was summarily ousted, but the damage was done. Fiala had packed the wrong supplies due to his inexperience, and Zahm’s narcissistic tendencies caused him to insist that boat pennants with his own seal be carried along, wasting crucial supply space. The intense descent down the Amazon tributary, the Rio da Dúvida, nearly cost Roosevelt his life and he never recovered his tremendous physical vigor he displayed during his presidency.

Conclusion

To recap, you are a valuable being created with appropriate limits. Recognizing this, and letting go of grandiose ideas of personal control allows for you to function on behalf of your organization with confidence. While there are often external limits placed on you and your organization, these limits contain within them the seeds of creative solutions. In day to day activities, your limits allow you to categorize your time for the most effective outcomes. There are times where leaders and visionaries bring their organizations intentionally into liminal spaces for creative thought, but this must be done with care and guidance. If limits are ignored, either through inexperience or narcissism, the consequences can be catastrophic.

Recommended books & resources mentioned in this essay:

- “The Bible” NIV

- “The Goal” by Elihu Goldratt

- Gift Mapping Workshop from Tim Gunsolley

- “The River of Doubt: Theodore Roosevelts’s Darkest Journey” by Candice Millard

- The Psychology Behind Liminal Space – Article: https://www.verywellmind.com/the-impact-of-liminal-space-on-your-mental-health-5204371

- “The Blind Side: Evolution of a Game” by Michael Lewis – Story shared through Sundays at Six an Email Newsletter by Billy Oppenheimer

- “Innovation for Social Change: How Wildly Successful Nonprofits Inspire and Deliver Results.” – by Leah Kral